Keep reading about similar topics.

In this article, we aim to expand your thinking about the cost of materials to account for the costs borne by individuals and fenceline communities who are exposed to toxic chemicals every day. The bottom line is that some products can be sold cheaply because someone else is carrying the burden of the true cost.

When you shop for a flooring product, what do you consider? Perhaps you think about the look and feel of the product and its durability. You likely also consider the price. The cost of using a material is influenced by the cost to purchase the product itself, the installation cost, maintenance costs, as well as how long the product will last (when you will have to pay to replace it). These are all internalized costs, paid by the building owner.

These costs alone, however, do not consider the full impacts of materials along their life cycles. More and more building industry professionals are paying attention to the content of building products and working to avoid hazardous chemicals in an effort to help protect building occupants and installers from health impacts following chemical exposures. To understand the true, full cost of a product, we must look beyond just the monetary cost of purchasing and maintaining a product.

Many of the costs associated with products are more or less hidden when choosing a building material. Just a few of these hidden costs are outlined below.

Toxic Chemical Impacts on Human Health

The US Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) estimates that American workers alone suffer more than 190,000 illnesses and 50,000 deaths per year that are related to chemical exposures. These chemical exposures are tied to cancers, as well as other lung, kidney, heart, stomach, brain, and reproductive diseases.1

While some workers may see greater exposures to hazardous chemicals, all of us are impacted. Many of you are likely familiar with PFAS, aka per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS have been used in a wide range of applications, including stain-repellent treatments for carpet and countertop sealers. The widespread use of PFAS has led to extensive contamination of the planet and people. Increasing research and attention to this group of chemicals has led to some quantitative understanding of the costs to society of their use. A recent publication in Environmental Science and Technology outlined some of the true costs of PFAS chemicals. The authors highlight that, “A recent analysis of impacts from PFAS exposure in Europe identified annual direct healthcare expenditures at €52–84 billion. Equivalent health-related costs for the United States, accounting for population size and exchange rate differences, would be $37–59 billion annually.” Importantly, they further call out the fact that, “These costs are not paid by the polluter; they are borne by ordinary people, health care providers, and taxpayers.”2

And this is just the cost of one group of chemicals. Another recent study estimated the cost of US exposures to phthalates, a group of chemicals used to make plastics more flexible, to be approximately $40 billion or more due to loss of economic activity from premature deaths.3 While more research is needed, the scale of these estimated costs is staggering.

Environmental Contamination Costs

The release of PFAS chemicals has contaminated water supplies globally. About two-thirds of the US population receives municipal drinking water that is contaminated with PFAS. Reducing the levels of PFAS in drinking water can be expensive, and none of the methods fully remove PFAS. In the Environmental Science and Technology study mentioned above, the authors note that “following extensive contamination by a PFAS manufacturer in the Cape Fear River watershed, Brunswick County, North Carolina is spending $167.3 million on a reverse osmosis plant and the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority spent $46 million on granular activated carbon filters, with recurring annual costs of $2.9 million. Orange County, California estimates that the infrastructure needed to lower the levels of PFAS in its drinking water to the state’s recommended levels will cost at least $1 billion.” Again, these costs are typically not paid by the polluter but shifted to the public.4

Climate Change Impacts

Chemicals used in the production of some PFAS are ozone depleters and potent greenhouse gases. New research released in September by Toxic-Free Future, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families, and Mind the Store ties the release of one such chemical, HCFC-22, to the production of PFAS used in food packaging. The reported releases of this one chemical from a single facility is equivalent to “emissions from driving 125,000 passenger cars for a year.”5

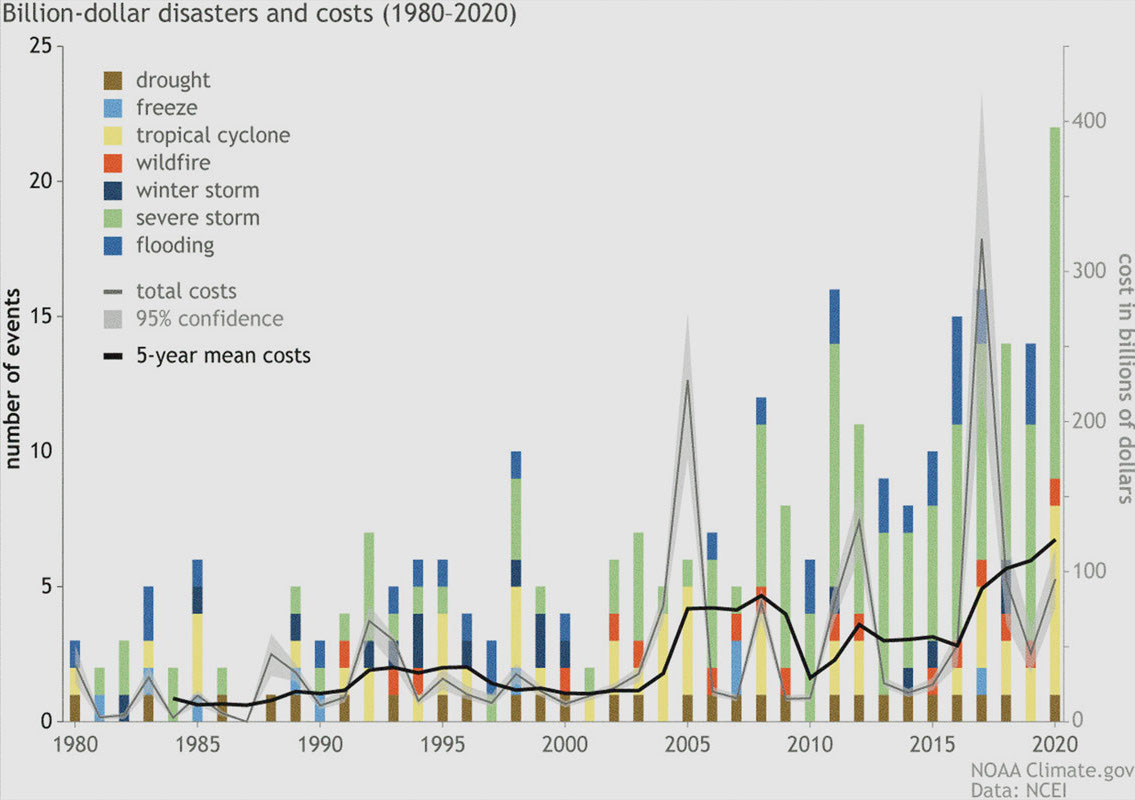

The costs of climate change impacts are immense. For example, the number of billion-dollar disasters and the total cost of damages due to natural disasters have been skyrocketing. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describes how climate change contributes to increasing frequency of some extreme weather events with billion-dollar impacts. They outline the broader context of these extreme weather events saying that, “the total cost of U.S. billion-dollar disasters over the last 5 years (2016-2020) exceeds $600 billion, with a 5-year annual cost average of $121.3 billion, both of which are new records. The U.S. billion-dollar disaster damage costs over the last 10-years (2011-2020) were also historically large: at least $890 billion from 135 separate billion-dollar events. Moreover, the losses over the most recent 15 years (2006-2020) are $1.036 trillion in damages from 173 separate billion-dollar disaster events.”6

Figure 1. Billion-dollar Disasters and Costs (1980-2020)7

Environmental Injustice

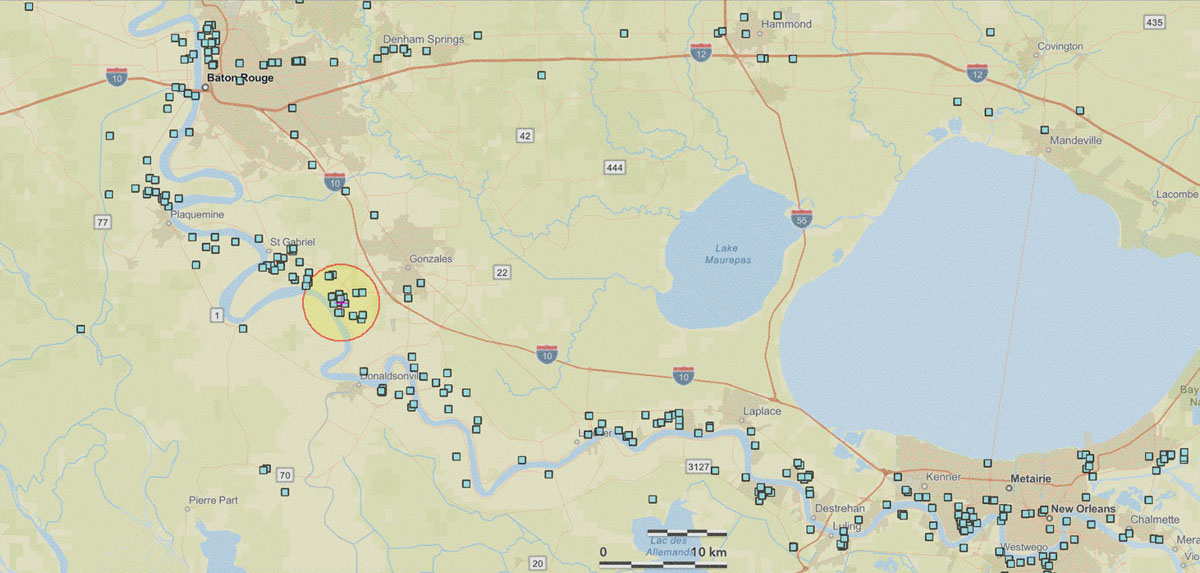

In the US, communities of color and low-income communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental pollutants.8 These communities often face hazardous releases from multiple sources due to high concentrations of manufacturing facilities near their homes. The area along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is known as “Cancer Alley” because of the concentration of industrial activity and the associated elevated cancer risks.9 Figure 2 maps facilities that report to EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) in this area. These are facilities that release or manage hazardous chemicals that require reporting to EPA.

The city of Geismar, LA is home to 18 TRI facilities. These facilities reported a total of over 15 million pounds of on-site releases of hazardous chemicals to air, water, and land in 2019.10 Several of these facilities produce chemicals used in the building product supply chain. Two facilities produce chlorine for internal or external production of PVC, which can be used to make pipes, siding, windows, flooring, and other building products.11 Two other facilities manufacture a key ingredient of spray foam insulation, MDI. Some of these facilities have a history of noncompliance with EPA regulations, one having significant violations for eight of the last twelve quarters and another having significant violations for all twelve of the last twelve quarters.12 Surrounding communities are impacted by regular toxic releases from these facilities and are vulnerable to accidents involving toxic chemicals. For example, an explosion and fire at the vinyl plant in 2012 released thousands of pounds of toxic chemicals, led to a community shelter in place order, and shut down roads and a section of the Mississippi River.13

More than 5,000 people live within three miles of one or more of these four facilities. This community is disproportionately Black — 35% of the population compared to 12% in the US overall. Thirty percent of the population is children, with about 1500 kids under the age of 18. This community has a higher estimated risk of cancer from toxics in the air than most places in the US — almost four times the national average.14

The message we hope you take away from this article is that we must move beyond discussions based purely on the material costs or up-front costs of products. We must all work together to acknowledge and shed light on the true costs that toxic chemicals have within our society and on specific communities. The impacts of hazardous chemicals are, of course, not just monetary –people’s lives are significantly impacted in multiple ways. The current system subsidizes cheap products by robbing individuals of the opportunity for healthy lives and for children to play, and grow up, and enjoy a full and normal life.

Unfortunately, there is not currently enough information available to make detailed cost accounting broadly possible, and no framework exists for accounting for and comparing the full extent of product costs. Transparency about what is in a product, how the product is made, and hazardous emissions – beyond those required to be reported by law – is critical. Programs that place extended responsibility on manufacturers to manage materials at their end of life (as part of extended producer responsibility or EPR)15 can be a starting point for conversations about the full life cycle impacts of products and can help hold manufacturers accountable for a broader array of costs, once they are better understood.

In the meantime, Habitable works to incorporate a life cycle chemical perspective into our safer material recommendations like our InformedTM guidance and Pharos database. Hazard Spectrums. These tools are a work in progress initially focused on avoiding hazardous chemicals in a product’s content. As a starting point, this helps protect not only building occupants and installers, but also others impacted by those hazardous chemicals throughout the supply chain. When hazardous chemicals are used, it is likely that someone throughout the supply chain is impacted. InformedTM can help you choose safer building products based on the information that we have today as we work to expand our incorporation of life cycle chemical impacts into our research and to provide guidance on a broader range of materials.

Habitable looks forward to continuing to identify and provide the critical data needed to assist in decision making with a more comprehensive view of the true costs of materials, and to developing resources to help communicate the collective return on investment seen by a society where all people and the planet thrive.